You launched a campaign that finally delivered. Lead volume went up across key segments, conversion rates improved, and sales started seeing higher-quality opportunities in their pipeline.

Everything pointed toward a healthy funnel and more substantial revenue potential, until you walked into the executive review.

That’s when the CFO flipped through your slides, paused for a second, and asked the question:

“What did this actually do for revenue?”

This is a very familiar moment. I have faced this multiple times.

The work might be strong. The metrics might be trending up.

But if the CFO doesn’t see how it all ties to business outcomes such as revenue, efficiency, and cash flow, your results don’t land.

As Niko Laine, former SaaS CFO and founder of MRR.io, puts it:

“We like spending money too. But we like burning it the smart way. We like to know what the return on investment is and when we’ll get it.”

That’s the gap.

Marketers tend to lead with metrics like impressions, MQLs, and engagement rates.

CFOs don’t.

They want to hear about CAC, CAC payback, LTV, pipeline impact, and how quickly marketing activities convert to cash.

When you can’t explain the connection between your work and those outcomes, you lose leverage. The budget becomes a line item to trim, not an investment to protect.

This blog is a tactical breakdown of how to close that gap.

Not just how to report better, but how to speak the language your CEO and CFO already use, so marketing gets seen as a driver of growth, not a cost center.

Why marketing gets misunderstood by the C-suite

The disconnect starts with language. CEOs and CFOs spend their time thinking about business outcomes.

They care about hitting revenue targets, extending runway, improving margins, and keeping forecasts predictable.

Their world is built around board decks, investor updates, and P&L statements. That’s the context they live in.

Marketing doesn’t always show up in that world.

Too often, it shows up with slides filled with impressions, open rates, engagement graphs, and funnel screenshots.

These numbers might be useful inside the marketing team, but they don’t map to how the business measures performance.

Executives don’t know what to do with an MQL.

They want to know how many customers marketing brought in, what those customers cost, how long it’ll take to earn the money back, and what kind of revenue they’re likely to generate over time.

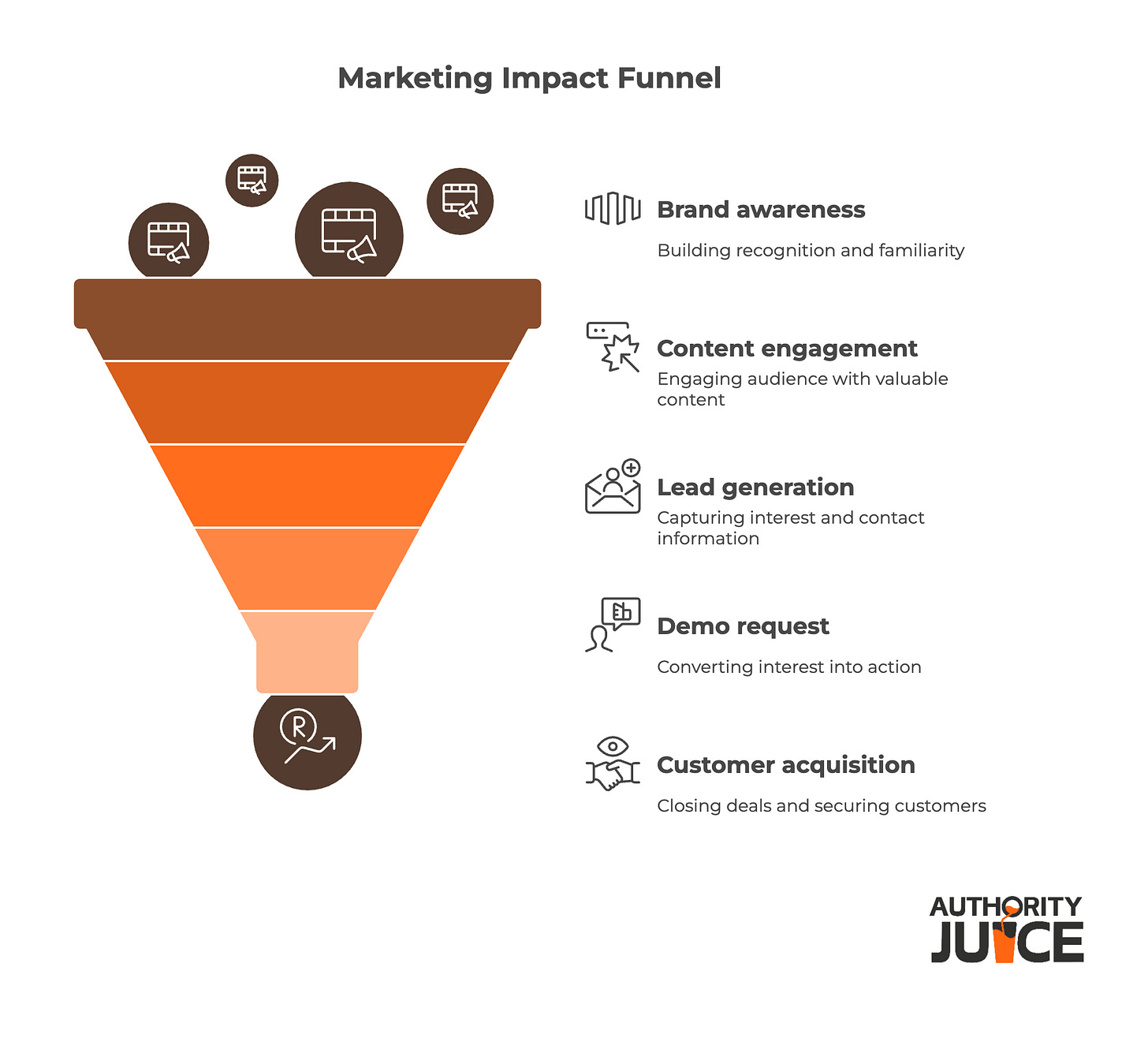

To a CFO, “brand awareness” means very little unless you can show how it leads to pipeline growth, lowers acquisition costs, or drives retention. The same goes for engagement metrics or top-of-funnel reach.

Without a financial connection, these numbers feel like fluff.

This is why so many CMOs lose credibility in executive conversations.

They talk in metrics that live inside marketing dashboards instead of talking in terms that live on a balance sheet.

And when that happens, marketing gets reduced to a cost center.

The language shift

Marketing metrics aren’t the problem. Reporting them without context is.

When you show leads without showing how many turned into sales opportunities, the number loses meaning. When you highlight website traffic without tying it to conversion or customer acquisition cost, it sounds like vanity.

What changes the conversation is the ability to connect marketing activity to financial results. Instead of leads, talk about qualified pipeline. Instead of traffic, talk about funnel conversion and cost efficiency.

When you can explain how your work lowers CAC or improves payback, you’re speaking their language.

The LTV:CAC ratio is one of the clearest ways to show marketing efficiency. A healthy ratio is 3:1 or higher.

That means for every dollar spent on acquisition, the company generates at least three dollars in lifetime revenue.

If your campaigns are bringing in high-quality customers with long-term value, that’s the ratio to showcase.

It tells the CFO what they need to know in one line: whether your efforts are compounding or just burning cash.

Pairing metrics is another way to shift the narrative. One number on its own often creates more confusion than clarity. For example, reporting LTV without CAC leaves the CFO guessing.

Reporting traffic without showing how that traffic converts doesn’t help sales forecast. When you pair these numbers — what some teams call “chopsticks metrics” — you build a full picture of performance.

Show them:

Cost and return

Volume and efficiency

Activity and impact

This is what earns more trust at the table.

Also check out: How to build a growth flywheel that doesn’t cost $50k/month ad budget

How to sell your marketing plan

A good marketing plan won’t sell itself at the executive table.

Most financial leaders look for clarity on inputs, confidence in outcomes, and visibility on timing.

That’s why the most effective structure for pitching your plan is the Input → Output → Timeline model. This approach mirrors how finance teams already think.

Start with the input. Outline the exact amount of money you need and break down where it will go.

A vague line item like “campaigns” doesn’t build trust.

A breakdown across media spend, tooling, and internal resources shows you’ve thought through cost allocation like an operator.

Next, connect that input to tangible business outcomes. Focus on marketing’s impact on pipeline contribution, CAC, payback period, or ARR growth. Skip the early-funnel metrics unless they directly influence one of these targets.

Then give a clear timeline. Be specific about when those outcomes will start to show. Most CFOs won’t expect immediate returns, but they want to see when each stage of impact will land. Showing how your plan plays out over 30, 60, or 90 days brings predictability into the conversation.

From there, go one level deeper and show how your plan balances risk. Treat it like a portfolio, not a monolith.

Some programs might drive fast returns through direct response. Others build long-term value through brand or content assets.

Present the full mix the same way a CFO might explain a blended investment strategy.

When you pitch a plan like an investment, executives listen differently. They stop trying to trim the fat and start asking how to help it scale.

You can add another layer of confidence by showing three possible outcomes.

Present a best-case, base-case, and worst-case view of performance.

This shows that you’ve already done the scenario planning.

Lastly, highlight leading indicators that will surface early in the process. This could include demo requests, engagement from high-fit accounts, or pipeline velocity improvements.

These signals may come before revenue hits the books, but they help execs track progress and stay aligned with your timeline.

Telling better stories (with numbers)

Data matters. But in a room full of decision-makers, numbers alone don’t win the argument.

Stories do. Especially stories that tie numbers to business outcomes.

This is where most marketers go wrong. They bring dashboards, but not narratives. They present campaign performance, but skip the part where that performance turns into revenue.

That’s a miss, because executives don’t remember metrics. They remember impact.

One of the simplest ways to shift perception is to reframe what marketing creates.

Most CFOs see campaigns as expenses — short-term costs with short-term returns.

But not all marketing works that way. Content and SEO, for example, behave more like assets. They generate returns over time.

A single blog post can drive inbound interest for years. A well-structured landing page can keep converting long after it’s launched.

This is why many SaaS CMOs compare content to capital assets on a balance sheet, not media spend on a P&L.

Brand works the same way. It rarely shows up in last-touch attribution. But it creates lift across every channel.

When done well, brand shortens sales cycles, increases close rates, and makes pricing less elastic.

It functions like equity on the balance sheet. It builds over time and protects the company’s value in down markets.

Compare that to lead generation, which plays more like the income statement. It brings in volume fast, and the impact is easier to measure in-quarter. Both matter. But they serve different financial purposes, and you need both to build a healthy pipeline.

Let’s say you closed a $500,000 ARR customer last quarter. Walk the exec team through the path: they discovered your brand through a webinar six months ago, read three blog posts, signed up for your product newsletter, and eventually came inbound requesting a demo.

This story proves that marketing didn’t just hand off leads; it created the conditions that made the deal possible.

The goal here isn’t to oversell or over-credit marketing. It’s to make the work legible.

Also check out: You’d be nuts to ignore vibe marketing

Reporting marketing results like a CFO

Every number you report should be compared to something.

Don’t just say you generated 500 leads. Say that you generated 500 leads, which is 12% higher than last quarter and 8% above target.

Or that you brought in $1.2M in pipeline from enterprise accounts, which exceeds last quarter’s segment performance by 30%.

Context earns credibility. Numbers in isolation invite skepticism.

Benchmarking also means reporting against industry standards.

If your CAC is 20% lower than the industry median for mid-stage SaaS, say so. If your payback period is under 12 months, which is typically considered a strong benchmark in B2B SaaS, that’s a headline.

These are metrics your CFO already cares about.

The next layer is transparency.

Don’t oversell. Don’t dodge questions.

Own what didn’t work, share what you learned, and show what’s already in motion to fix it.

A missed goal doesn’t undermine your credibility. Avoiding it does.

CFOs are risk managers. They don't expect perfection. But they expect honesty. When you’re clear about what didn’t land and specific about how you’ll adjust, they start to see you as someone they can trust, not just a department trying to justify spend.

The third piece is ROI, and it has to be in terms they recognize.

Show the return in dollars and time. Don’t say “the campaign performed well.” Say “we spent $50K and generated $200K in new ARR, with a 6-month payback period.”

Or that your customer community initiative led to a 10% lift in retention, which translates to $1.4M in projected ARR savings over the next 12 months. This is how you turn marketing from activity into business performance.

Keep your reporting structure simple. You don’t need to show every metric. You need to show the few that matter most. A strong executive dashboard should focus on things like:

Marketing-sourced pipeline ($)

CAC and CAC payback

LTV:CAC ratio

Contribution to revenue targets

Movement in key leading indicators (e.g., demo requests, conversion rates, churn lift)

Avoid the trap of throwing in 15 KPIs to prove how much you’re doing.

You don’t need to speak finance fluently. But you do need to make marketing legible to the people who protect the budget.

The campaigns, the content, the brand work…they all matter. But at the executive table, what matters more is your ability to translate that work into language your leadership team already trusts.

Great marketers know how to build demand. Great marketing leaders know how to show what that demand is worth — in dollars, in time, and in margin.

The next time you walk into a boardroom, don’t bring a slide full of MQLs. Bring a clear answer to how marketing is driving the number.

Then bring coffee for your CFO. They’ll be wide awake by the time you’re done.

P.S. 👀 I usually open up 5 free slots each quarter for founders and CMOs who want a no-nonsense, organic marketing audit. I’ll give you real feedback on what’s working, what’s not, and where you’re leaving revenue on the table.